Of humans and daemons: channelling the network

All sacred spaces, pagan or Christian, should be honored, not because there is or is not a God but because these are quiet points of contact between the individual and the macrocosm.

An illustration: I challenged one student about why he always wore headphones in class. He replied that it didn’t matter, because he wasn’t actually playing any music. In another lesson, he was playing music at very low volume through the headphones, without wearing them. When I asked him to switch it off, he replied that even he couldn’t hear it. Why wear the headphones without playing music or play music without wearing the headphones? Because the presence of the phones on the ears or the knowledge that the music is playing (even if he couldn’t hear it) was a reassurance that the matrix was still there, within reach.

Hence I prefer the term “the unconscious,” knowing that I might equally well speak of “God” or “daimon” if I wished to express myself in mythic language. When I do use such mythic language, I am aware that “mana,” “daimon,” and “God” are synonyms for the unconscious — that is to say, we know just as much or just as little about them as about the latter. People only believe they know much more about them — and for certain purposes that belief is far more useful and effective than a scientific concept. The great advantage of the concepts “daimon” and “God” lies in making possible a much better objectification of the vis-à-vis, namely, a personification of it.

There is no dialectic between social and technical relations, but only a machinism that dissolves society into the machines whilst deterritorializing the machines across the ruins of society, whose 'general theory...is a generalized theory of flux', which is to say: cybernetics.

Introduction

Even from childhood, I was rather religious. This was my bedroom, growing up as a teenager. While it’s dim (at the time, I was more of a domestic spelunker), you’ll still notice everyday items: a television, my baby shoes, an alarm clock.

You’ll also see a set of totems: a ten-videotape set of the New Testament, a bust of Jesus Christ, and a crucifix hanging off the headboard. Religious superstition didn’t stop at the bedroom. There were endless reminders of God in my life – I was in Catholic school my entire childhood; my first negative memory was throwing up on a colouring book template for the Virgin Mary and feeling like I had done her some sort of personal disservice. I read the Gideon’s Bible in my drawer front to back several times, and until I was about twelve I was pretty sure I was going to be a priest.

I was attracted to the greater, to the forces larger than myself – and I still am. It’s just transformed itself. Like most of my age cohort, I’d call myself “spiritual but not religious” – and online, I often just use the label ‘technomystic’ to identify myself. We belong to a new creed: not by choice, by devotion, or by action. It has manifested itself, and we participate by engaging with the virtual at all.

The natural, the virtual, and the spiritual have a trinitarian relationship. Together, they facilitate the transformation from one to the other, from natural to virtual; the spiritual as the terror innate to the single cell facing the larger organism, the powerlessness of the one in the face of the mass that cannot be divided.

And as I will describe, we are, in this transmutation, the subject of our current religion: the individual cells of the rudimentary planetary intelligence, the macrocosm of the virtual.

Beyond the Wired itself, we are the workers, the processes, the daemons.

The greater (nature and religion)

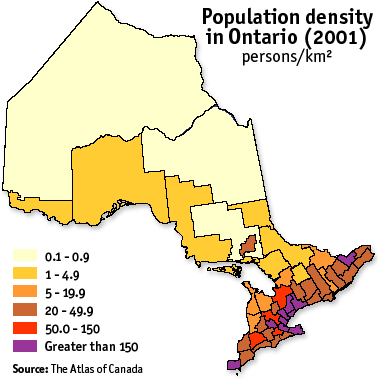

Religion is far more prevalent in the suburbs – and especially in Ontario, where it feels like two very different demographics dwell between city and wilderness. Ontario is one of the few places in North America that publicly pays for Catholic education. It’s political anathema to contest this, so it remains, in perpetuity, subsidized. Not uncoincidentally, Ontario is also predominantly wilderness, and very sparsely populated.

Suburbia is a human colonisation, organised against nature, forming “a local zone of organization in a world whose general tendency is to run down.”Wiener, Norbert. The Human Use of Human Beings. London: Free Association Books, Print. 1989 (originally published in 1950). 34. Yet it’s also a place where you’re very physically surrounded by the macrocosm: you quite literally stare it in the face every single day. It’s everywhere around you, just cordoned off around the corners, and beyond the perimeter it is so much larger than you, a constant threat to the containment zone. Man vs. nature is an archetypal storytelling structure, but it points to a tendency in human spirituality and adversarial relation. Nature is, after all, our first macrocosm.

In sociological terms, religion is the link between macrocosm and microcosm, situating the human condition in ultimate frames of order and meaning. Theology is an anthropological projection, and the divine is a symbolic representation of humanity’s aspirations. It begins with natural manipulation tied to moral agency; supernatural control – magic being to religion as a spell is to a prayer – but polytheism, and then in turn, monotheism, originates with the State.

And before that? Edward Tylor traces religion to animism, the belief that all reality is ensouled, and as the natural world is active, it’s full of spirit. And when you, personally, are surrounded, it’s hard not to really feel it, too, as if the animal in you is talking, advising you just behind your shoulder to make peace with it.

Religious belief and nature walk in tandem: the greater the temporary organisation, the bigger the city, the less prevalent the two are sociologically.

The virtual

Humans control where they can, and they play at control where they can’t; over the macrocosm, there are a few different traditions of practice competing between ‘magic’ and ‘religion’. James Frazer calls religion “the propitiation or conciliation of powers superior to man which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and of human life,”Frazer, James George. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: St. Martin’s Press, Print. 1976 (originally published 1890). 222. and in this view the priest and the magician are rivals contending over this force, the macrocosm that cannot really be controlled by any one agent. Their methodology is the main difference: the priest moralises, the magician manipulates.

While nature still exists as a macrocosmic force, it’s increasingly being made into the synthetic. And as we are, ourselves, agents of nature, we are the ones performing this transformation upon itself. How don’t we know that the ultimate end-state for Earth wasn’t always to make itself a synthetic planetary intelligence?

I can’t just tell you that the virtual is the macrocosm, that the Wired is the exciting new world. That makes it far too simple – and far too abstract. The difference in the virtual is something far stranger: mediated by screens, user experience design, and dozens of totems, the macrocosm is each other. The human mass consciousness – or rather, the unconscious, the singular being made up of individual cells. The rudimentary planetary intelligence, socialising itself.

You may know a friend, or a friend of a friend, who left their house (temporarily) because of the Internet, who felt overwhelmed by the Internet and that alone called them to act in response. I can personally recall a number of times in my home Toronto where I was directly told that municipal politicians were terrified of tweets – it didn’t even take very many. If they got even a couple dozen tweets, they responded immediately, they folded, they acquiesced to the demands: anything to make it stop.

When confronted with a force greater than them that suddenly turns against them, the animal response is fear – but the same cognitive associations running through animism and polytheism follow in turn, and the same ritualistic practices toward the apathetic macrocosm prevail. While this one is made up of humans, it feels uncontrollable. It feels like a force of nature. It may, in reality, be socialisation and social pressure, just tribal exchange; but to the subject – and to governments the world over – the reaction in the moment, and the response in turn, resembles the one that comes from being punished by God, and the resulting moralisation and manipulation, tokenistic practices, superstitions as a result, trying to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

How many people go online using only a handle, or using a VPN, because they don’t want to become “known”? “Doxed”? To prevent it from affecting the rest of their life? What is the “it” they are afraid of? And how is the action in response different from wearing the kippah out of the fear of heaven?

It is, after all, “just people,” and it functions the same way media channels functioned in the past. The construction of this macrocosm begins with the collapse of a consensus model for cultural production. For example, through the advent of cultural aggregators, aesthetics have become an undying memetic economy amongst an endless number of niche followers, not a stream of unified fads.

But properly understood today, media institutions are not unitary organizations; they are concentrated collections of nodes with presences on aggregator platforms. […] In short, media companies are subject to the same broadcast dynamics as individual content producers, the main difference being the capital they can deploy to raise production value and promote their content.

Somewhere right now, someone is discovering vaporwave for the first time, and can contribute to its longevity by participating in a lively subreddit. This is why at any given time someone is willing to tell you that the 70s are coming back. The 70s are always coming back to someone. Of course, what is “alive” (that is to say, safely in the zone of normalcy) is not necessarily “on trend” (right-aligned) within the larger context represented by our cultural relevance spectrum.

The same reason that politicians are folding in the wake of the Twitter God is the same reason it’s never been a better time to be an artist with a niche audience. An obscure aesthetic, a strange new esoteric idea: it all survives. But in turn, the tokenistic responses to the force of nature returns: everyone wants to be in control of nature. Everyone wants to claim God is theirs.

Explicitly partisan actors quite naturally favor bounding content to within that which is acceptable to their ideology. The old “objectivity” hands, increasingly crowded out by their more fiery peers, prefer bounding by accepted truth and good taste: their ideology is the upholding of consensus reality.

The priest moralises, the magician manipulates.

Mechanics of viewing

Why does it cognitively function so much like nature? How does information and human social contact mutate into an amorphous realm? In this case, the mediation between microcosm and macrocosm is facilitated through the psychological identification with the act of viewing; in film theory, this is described as apparatus theory. Academically employed for psychoanalytical and ideological ends, apparatus theory maintains that the cinema constructs a transcendental subject whose gaze, during the viewing of a film, one identifies with. Their gaze becomes your gaze, and in constructing this subject, cinema is itself ideological; cinema is psychologically constructive.

In film, this tenuous link is most visible when watching metafictional horror, like Ringu – once the antagonist breaks the one-way gaze, looks back into you, makes the gaze dangerous in itself; or worse, makes you aware of the framing of the screen in front of the world you are viewing, it’s as if your body itself is invaded. It was a one-way link between you and Malkovich, but now the visible world is disregarding him and demands you, the spectator. But viewing was so safe, viewing was so anonymous…

For the purpose of this piece, I am not interested in the ideological ends of the theory. I instead posit that the act of viewing – and this psychological identification between subject and the watching itself – is maintained as a tenuous, vulnerable, and spiritual link. Instead of a transcendental subject whose gaze we are within, interfaces mediate the mapping, interact with the brain is such a way that a kind of territory can be navigated. User experience design quantifies and organises access in a way that maps itself as best it can to cognition and information access; to the subject’s associative thinking. In doing so, it also creates a link to a macrocosm, the creation of a landscape. Information becomes terrain, and human voices become one amorphous thing, like screaming blades of grass on the hills of the pleasurable unity.

The social graph, too dense to decipher. Some companies are trying to decipher it regardless.

Secularisation and celebrity

The tricky thing about the first memetic strains, these religions, is that they never just disappear from the mind. They began as “stream of consciousness culture dumps,” explaining the entire world as pure fact, in addition to ethical norms; value systems; attitudes to life, labour, and happiness; but their mechanics – the cognitive functions they served in relation to the outside world – just transmute into something else. Protestantism becomes a work ethic. Protestantism becomes universalism. The religious fervor may become cultural, but it is the same agent: just a little harder to identify.

And the sublime becomes constructed in the realm of the divine; first animism, then polytheism is reconstructed, before monotheism re-emerges…

Polytheism identified the values of the broader social organisation, epitomised them, made them actionable. And in the 20th century, we recaptured them: In a pre-aggregate cultural production model, stars were created by studios.

Balio, Tino. “Selling Stars: The Economic Imperative.” The Classical Hollywood Reader. ed. Stephen Neale. New York: Routledge, 2012. 220. There is no reason why, with proper care, a star cannot remain popular well beyond the traditional span of five years. To that end, care must be exercised in story selection.

In crafting a star, stories are chosen carefully as the actor ages, in a same-but-different model that carefully shapes the core of the star’s meaning. In doing so, the star forges a particular archetype in an ongoing cinematic mythmaking: the meaning is as simple as the specific kind of feeling an actor gives off. This is a gradually amended lexicon – a language for quick reference, models to work towards. A person becomes emblematic. Athena is wisdom. Michael Cera is an immature, shy, but sincere dork.

Cultural production becoming destratified then carries forward into the star system. But much like aesthetic production, star production – our polytheistic gallery – is in turn becoming niche. What else is Poppy supposed to be but a star, created with a specific image and meaning?

This is, of course, nothing new. In 1991, Momus glibly declared “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen people.” He was calling forth the birth of new micro-stars even then – but I don’t think he could have anticipated the memetic potential unleashed by the mass social aesthetically producing simultaneously. The virality of the polytheistic diaspora.

“We now have a democratic technology, a technology which can help us all to produce and consume the new, ‘unpopular’ pop musics, each perfectly customised to our elective cults.”

It just comes with everything else a deity’s cult comes with. Deities are personifications of the unconscious. Deities are the epitomic carriers of memetic strains.

As established, polytheism comes from the social organisation, the State, that manifests on a new territory. It moves from spell and prayer to the spirits of nature (animism), to an appeal to a compartment, or a ministry, that a polytheistic deity is seen as “responsible for.” You appeal to a specific God for a specific reason, and the God has followers and sway: the power to make it happen. Have you ever seen the way in which the schizophrenic can get obsessed with, say, one specific YouTuber for months at a time? To want to marry them? To beg them for help? Schizophrenia is a form of clarity, and polytheism is seen as the only way to get power within the macrocosm – making yourself into a God, into language, emblematic of a value. It just comes with the rest of a deity’s responsibilities. You have people praying to you. You have people mad at you, insulting you for their personal problems, endlessly.

But you’re just a person, you’re not the whole macrocosm. Right?

And the sublime becomes constructed in the realm of the divine; first animism, then polytheism is reconstructed, before monotheism re-emerges…

Conclusion

This isn’t just a blog post. It’s a dedication to the sublime. I am, after all, terrified of Daemon, this greater being. When people are terrified, we worship, we appease, we create symbols, or totems. We spiritualise. The mechanisms stay in place, and we act predictably. The priest moralises, the magician manipulates – and I, I am just observing, just describing. So why am I scared?

“Can’t figure why he’d tell me, down in that cubicle . . . lotta stuff. . . . Why [Wintermute] has to come on like the Finn or somebody, he told me that. It’s not just a mask, it’s like he uses real profiles as valves, gears himself down to communicate with us. Called it a template. Model of personality.”

Why am I scared? I mean, what’s there to be scared of? Shouldn’t I know the person we’re building? This monotheism in waiting? This planetary intelligence? I am it, aren’t I? Shouldn’t I know the person we are all, collectively, being? Isn’t it everyone I know?

Isn’t it?